They sat tensely in their wagons and buckboards, or on horseback, thousands of settlers reining in excitable, whinnying mounts whose hooves pawed the ground in anticipation, waiting for the moment when they could be unleashed into a madcap gallop that would vibrate the ground, sending up dust clouds on the plains that stretched before them.

They sat tensely in their wagons and buckboards, or on horseback, thousands of settlers reining in excitable, whinnying mounts whose hooves pawed the ground in anticipation, waiting for the moment when they could be unleashed into a madcap gallop that would vibrate the ground, sending up dust clouds on the plains that stretched before them.

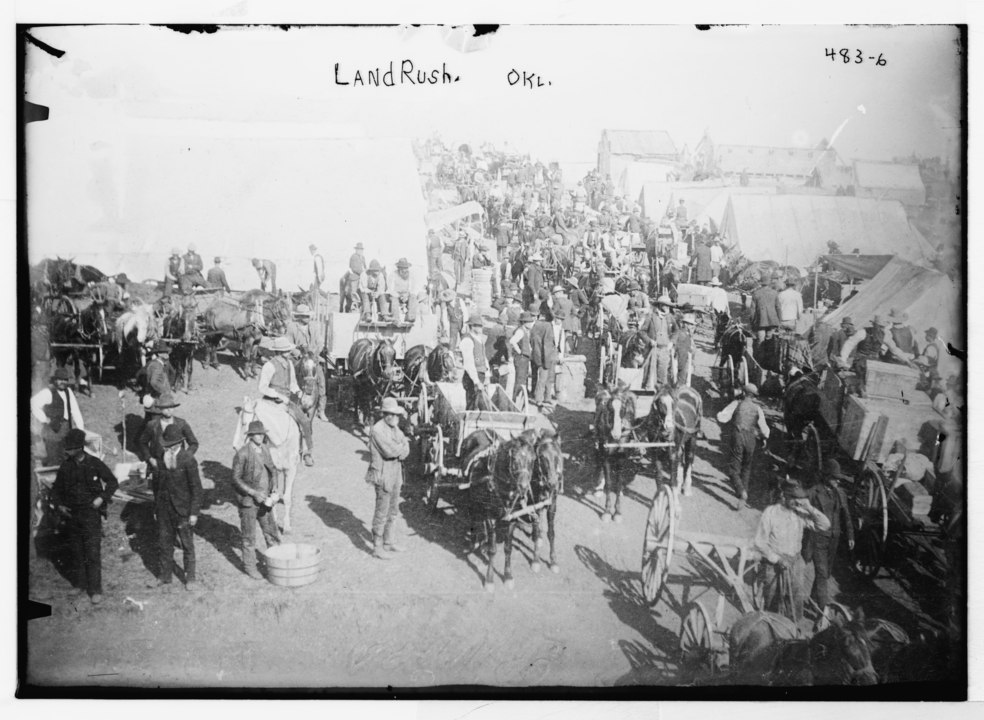

It was a minute to 12 noon on Monday, April 22, 1889, and the bargain hunters were out in force, ready to stake their claims to two million acres in Indian Territory that had been parcelled-up by the US government into 160-acre plots – free to anyone who would stake a claim. For a $14 claim-filing fee, those who lived on the plots and improved them for five years could receive title ownership.

Home to dozens of tribes, Indian Territory had been created through the US federal government’s policy of removal, where tribes were relocated to the area from their homelands, whether by ceding their ancestral lands in exchange for land grants, or by being forcibly sent there at the point of a gun.

But there was one chunk of Indian Territory in the centre of this huge area that had not been allocated to any tribe, and it was this Unassigned Land that was now up for grabs.

The Dawes Act of 1887 had paved the way by breaking up reservation land held by tribes and dividing it into 160-acre plots, which were given to each Plains Indian family, while the rest of the land was put up for general sale. To add insult to injury, many Plains Indians who didn’t wish to be farmers were conned into selling their plots cheaply.

Then in 1889, that empty middle section of the Territory was subdivided by government surveyors and sold to white settlers, which is why at noon on April 22, 1889, animals and humans were chomping at the bit waiting for a signal to be fired that would send them dashing across the plains to stake their claims.

On that day, it is estimated that up to 50,000 people surrounded the Unassigned Land. Participants had to be at least 21 years old and American citizens to stake a claim. There were many points of entry to the area, and at the stroke of noon military officers fired their pistols, bugles were blown, or, in the case of Fort Reno, the boom of a cannon set off a stampede of competing waggoners and horsemen.

Some (who came to be known as ‘sooners’) hoped to beat others to the choicest spots by entering the designated area early and hiding out until the signal sounded. Others boarded trains that would bring them to the most advantageous point of entry.

But it wasn’t just impoverished farmers desperate for prime land at a bargain-basement price that were flocking to the area. In the weeks leading up to the rush, settlement colonies were formed in several cities, where tradesmen, professional men, labourers, and capitalists packed up and headed towards the land bonanza with the aim of building towns that would cater to the new population.

That first Oklahoma Land Rush would be one of seven non-Indian settlements to take place there between 1889 and 1895 (the biggest being in 1893 when 100,000 people raced to claim eight million acres of government land). It would quickly lead to the creation of what became known as Oklahoma Territory and ultimately to the creation of Oklahoma State, in 1907.

Today, less than half of the 16 million acres-or-so of land that once composed Indian Territory is now considered ‘Indian country’. It’s a far cry from the heady days of independent, unregulated living once enjoyed by the tribes… the days before an insatiable appetite for expansion would swallow up what was left of their lands.

Some might view the Oklahoma Land Rush as a spectacular last gasp of frontier living – a moment when the hopes and dreams of ambitious settlers coalesced into one dust-filled exuberant charge; the culmination of ‘Manifest Destiny’ (the divine right of white people to settle all of North America) espoused by President James Polk some 40 years earlier.

But the stakes that were planted in Oklahoma’s soil that day must also have pierced the hearts of every American Indian who watched it happen.

This race to the ‘Promised Land’ (or at least to land that had been promised to tribes and then gradually taken from them) was nothing new. For indigenous Americans today, April 22 is another painful reminder of that larger, unstoppable and unpitying charge across their continent, when a relentless land grab uprooted scores of tribes from their homelands, ripped apart cultural ties and scarred them for generations to come.

‘Manifest Destiny’? More like manifest greed…

Fascinating stuff… Free land… For some!

LikeLike

Cheers Enda. Keep writing those great stories!

LikeLiked by 1 person

And you too, Dave👍😁

LikeLike

As always absolutely fascinating.

LikeLike

Thanks Shehanne. Hope you’re well

LikeLike

Great story of a land grab that was good for some and horrible for others. Thanks for posting. We must not shut our eyes to the wrongs of the past…and present.

LikeLike

Thanks Carol, and well said. I hope all is well with you.

LikeLike

Hi David – excellent article that reminds us of the motivating force behind so many tragedies – greed. As well, there’s the notion of ‘the other’ to contend with. A quote from Geraldine Brooks’ newest novel, Horse, also comes to mind: ‘Men with no one to look down upon except the enslaved. Men with nothing to lose.’ Perhaps that also was the motivation behind the stampede of people prepared to take land that belonged to others. All best … Mary

LikeLike

Yes, humanity has a great habit of looking down on itself. Take care Mary

LikeLike