Myles Joyce muttered a stream of Gaelic as he walked bareheaded through the prison gates, escorted by two warders. It was just after 8.15am on December 16, 1882, and Joyce had only a few minutes left to live… the scaffold awaited.

He was repeating in Gaelic the responses to prayers which were being read by the Rev Mr Grevan. But he was saying other things, too, which were later translated by some of those present.

‘I am going before my God. I was not there at all. I had no hand or part in it. I am as innocent as a child in the cradle. It is a poor thing to take this life away on a stage, but I have my priest with me.’

He was one of three to be executed. As he stood on the trap door his mind must have been a flurry of desperate sadness at the injustice of it all. Then the lever was pulled by the executioner William Marwood, and Myles Joyce dropped… to dangle like a final exclamation mark for all that had led to this sorry moment.

*

Myles Joyce, who was wrongfully executed

Maamtrasna is the highest peak in Connemara’s Party Mountains on the Galway-Mayo border. The Srahnalong River runs southwest from it to the shore of Lough Mask. On the south bank of the river sits a townland whose residents eked out an existence rearing sheep in the tough windswept conditions, and it is here that the tragedy which befell Myles Joyce had its origin.

On August 18, 1882, at a cottage by the lake’s shore, a scene of true horror revealed itself. The front door to the dwelling had been broken from its hinges. Inside, the walls were pockmarked with bullet holes.

The head of the household, John Joyce lay naked and dead on the floor, shot twice. Bridget, his wife, was on a bed, skull crushed above the right eye. Beside her was her son, Michael, still clinging to life after being shot twice. He would soon succumb to his wounds.

Another room revealed further carnage. Bridget’s mother, Margaret was also dead. A deep wound to her forehead signalled the cause. She had been stripped. Peggy was next ‒ a girl in her mid-teens, she had been bludgeoned to death.

Finally, beside her, lay Patsy, a boy of 12 who was found with two wounds to his head. He was still alive… and terrified. His older brother Mairtín was spared the horror – he’d been away during the attack, working as a farmhand in a neighbouring parish.

It was presumed that the motive for the slayings was somehow connected with stealing sheep.

What happened inside those walls at Maamtrasna not only shocked the community of 250 people who lived beneath the mountain but stretched all the way across to London.

A report in The Times two days later conveyed the mood…

‘No ingenuity can exaggerate the brutal ferocity of a crime which spared neither the grey hairs of an aged woman nor the innocent child of 12 years who slept beside her. It is an outburst of unredeemed and inexplicable savagery before which one stands appalled and oppressed with a painful sense of the failure of our vaunted civilisation.’

Ireland’s farmers were not exactly unfamiliar with agrarian violence. Just three years earlier, the Land League had been founded to fight for tenant farmers’ rights.

The battle was non-violent to a degree – co-ordinated non-payment of rents and the ‘boycott’ of certain landlords, coupled with highly effective political campaigning through the leadership of Michael Davitt and Charles Stewart Parnell.

But violence was also part of the arsenal, and landlords and land agents were soon targeted for attack. Several were murdered. In fact, seven months before the Maamtrasna killings, two men who worked for local landlord Lord Ardilaun had been murdered, their bodies dumped in the icy waters of Lough Mask.

In May 1882, the British government was left reeling with the news that its newly appointed Chief Secretary for Ireland, Lord Frederick Cavendish and Under Secretary Thomas Henry Burke had been murdered in broad daylight while travelling through the Phoenix Park in Dublin.

The air was febrile as the British introduced draconian policing measures to stabilise what seemed imminent anarchy. There was a sense amongst the British establishment ‒ exemplified by the anti-Irish cartoons in the satirical magazine Punch ‒ that there was a latent savagery in the Irish as a whole.

Then, as if to confirm this prejudice, came the Maamtrasna murders.

Maamtrasna murder accused

The police soon had an extraordinary break. Victim John Joyce’s cousins – brothers Anthony and Johnny Joyce and his nephew Paddy told police they had crucial evidence.

They gave statements to the effect that they had followed a group of ten men who had gone to John Joyce’s home. From their hiding spot in nearby bushes, the three cousins said they witnessed the group break down the door; some had then entered the cottage and much screaming ensued.

Anthony Joyce named the ten, and they were subsequently arrested and charged.

All the accused were Gaelic speakers. None could speak the Queen’s English – a fact that only added to the sense amongst the ‘civilised’ British Establishment that they were dealing with a bunch of ignorant barbarians.

The men’s solicitor – a 24-year-old graduate from Trinity College – could not speak Gaelic. The case was heard in the English language. Myles Joyce and his co-accused had no real idea what was going on.

British ‘justice’ rushed to make an example. Eight of the men were soon convicted, three of them receiving the death penalty for their part in the murders.

Not only did the accused not have the ability to defend themselves against the accusations, but witnesses were also bribed to ensure the ‘right’ verdict was reached.

Myles Joyce (left) and Tom Casey, the man who wrongfully accused him of murder

While researching his book on the subject, Éagóir author Seán Ó Cuirreáin discovered that Earl Spencer, the then Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (the country’s highest-ranking official) had been involved in secret payments to three witnesses in the case, giving them £1,250 for their ‘service’ (the equivalent of €160,000 in today’s money).

Before Myles Joyce’s walk up those scaffold steps, the other two men facing death admitted separately that they were guilty of the crimes, but they said that Joyce was innocent.

At the time, this was deemed insufficient to prevent or even postpone the execution and, so Myles Joyce was executed alongside them.

To make matters worse, if that were possible, the execution was botched. A Times reporter present on the day wrote that the executioner, Marwood, had to intervene when it came to Joyce’s death. Following the drop, Joyce was still alive and Marwood was heard to mutter in irritation and manipulate the rope to hasten death.

It was slow in coming. While the Death Certificates for the other two men, Patrick Casey and Patrick Joyce, is given as “Fracture of the neck being the result of hanging”, in Joyce’s case “Fracture of the neck” is scored out and the entry gives the cause of death as “Strangulation being the result of hanging”.

Even in death, there was no justice for Myles Joyce.

Two years later, in August 1884, beset by remorse, one of the witnesses, Tom Casey, approached the altar of the church in Tourmakeady during Confirmation Mass by the archbishop of Tuam, Dr John McEvilly, and admitted that he had been responsible for the death of an innocent man. He claimed that Myles Joyce, and four of those imprisoned were not guilty.

Meanwhile, journalist and Member of Parliament, Tim Harrington had met some of the men in prison when he himself was convicted for participating in anti-eviction protests. He soon became convinced of their innocence.

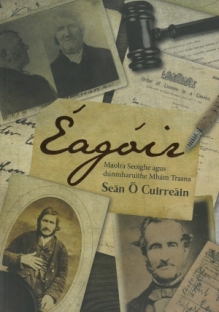

•Éagóir by Seán Ó Cuirreáin is published by Cois Life

According to Ó Cuirreáin: “Harrington did all the good things an investigative journalist would do, visiting the area with two priests in 1885.

“He even named the instigator, who was never charged, because the British government couldn’t contemplate having to admit to convicting innocent people.”

Following his investigations, the MP claimed that the Crown Prosecutor for the case, George Bolton, had deliberately withheld evidence from the trial.

The accusations caused a sensation in both the press and in parliament, with Parnell demanding an inquiry into the handling of the case. Prime Minister William Gladstone would not budge, despite damning evidence that a miscarriage of justice had been committed.

Flash forward to 2011 and, finally, two British peers ‒ Lords Lubbock and Alton ‒ asked for the case to be reviewed. Alton was keenly aware of the miscarriage as his mother was a Gaelic speaker from Maamtrasna.

In a subsequent documentary about the case, Alton spoke about the injustice that had been meted out.

“To have a fair trial, you need to be able to understand the evidence being given by your accusers, and you need to be able to understand the directions of the judge.”

An official review of the case was carried out and it was found that Joyce was “probably an innocent man”, but there was no talk of an official pardon from Britain.

The Irish State launched its own review in 2015, the results of which have recently been published and which found several factors, including witness statements and the processes and procedures around the trial, had led to a miscarriage of justice.

Ireland’s President Michael D Higgins has long been convinced that Myles Joyce was innocent of all charges. He intends to issue a presidential pardon – the first such pardon ever relating to an event that occurred before the foundation of the State.

“Everything that happened at the level of the State was horrendous. There was bribery involved. The accused didn’t get a proper chance to defend themselves. There wasn’t an atmosphere of equality and there was no equality as regards legal processes at that time,” he said.

It may have taken 136 years, but it finally looks like Myles Joyce will get the justice he undoubtedly deserves, and which was so sadly lacking all those years ago.

Terrific read Dave. A sad tale very well told.

LikeLike

Thanks Enda. Yes, very sad indeed. I love your blog by the way… keep scribbling!

LikeLike

Very moving story; I hope the Presidential Pardon causes it to become more widely known. I looked up the Death Certificate and it suggests that even in death a further misfortune befell Myles Joyce. The cause of death of the other two men who were killed that morning, Patrick Casey and Patrick Joyce, is given as “Fracture of the neck being the result of hanging”. But in the case of Myles Joyce “Fracture of the neck” but this has been scored out and the entry gives the cause of death as “Strangulation being the result of hanging”. It seems that the hangman botched the execution and Myles Joyce suffered a slow lingering death.

LikeLike

Thanks Patrick. I did come across a reference to some issue with the execution. I appreciate the added information. Regards David

LikeLike

When you look at the photo of Joyce and Casey side-by-side, it’s strange how much the accuser looks like the accused. Was it really Casey who was involved in this horrific crime? This was a sad but very interesting story, as most of yours are. Fortunately, in most civilized societies today, justice is dispensed in a more equitable manner.

LikeLike

Hi Dave, I hope you’re keeping well and still writing away. You’re right, they do look similar. Both men look haunted – one because of the unjust death awaiting him and the other for causing it to happen. I wish I could agree with you about justice being dispensed much more fairly these days. The same mistakes are still often made. History doesn’t seem to teach the Legal system very much, unfortunately.

LikeLike

Loved reading this, Mr. Lawlor. Let justice be served, after all.

LikeLike

Indeed Claire… and let’s hope it doesn’t take too long to come. Great to hear from you. I hope all is well. Take care, David

LikeLike

Wow .. what a story, David. I’m chilled just reading it. The corruption is unbelievable. Hope you are well.

LikeLike

Yes, terrible stuff. Greta to hear from you Mary.

LikeLike

A fascinating and heart-rending account of harsh (in)justice. The executioner was known as ‘Botcher’ Marwood in some circles. So sad that this awful end happened to an innocent man.

LikeLike

Thanks Denise. I think Mr Marwood deserves a bit more attention if he managed to get a nickname like that.

LikeLike

Oh how sad, how mad, history can be! What a splendidly written account of a wretched tale. It sets my teeth on edge. Thanks for this, David, and you need to anthologize these blogs into a book!

*All the accused were Gaelic speakers. None could speak the Queen’s English* which added to the view of them as *a bunch of ignorant barbarians* – and the *witness statements and the processes and procedures around the trial…Everything that happened at the level of the State was horrendous. There was bribery involved…* Yet there was a priest, and there was the condemned man, praying, in his final hour, and like Joan of Arc, how many years must pass before the innocent’s name is cleared? This is why I watch idiotic cat videos. The truth is unbearable!

LikeLike

Thanks Carol. It is such a sad case, the poor man. It’s really great to hear from you. I should have been in touch but I kinda dropped off the radar for a while. I hope you’re well… genuinely glad to be in touch with you again. Take care.

LikeLike